1/1

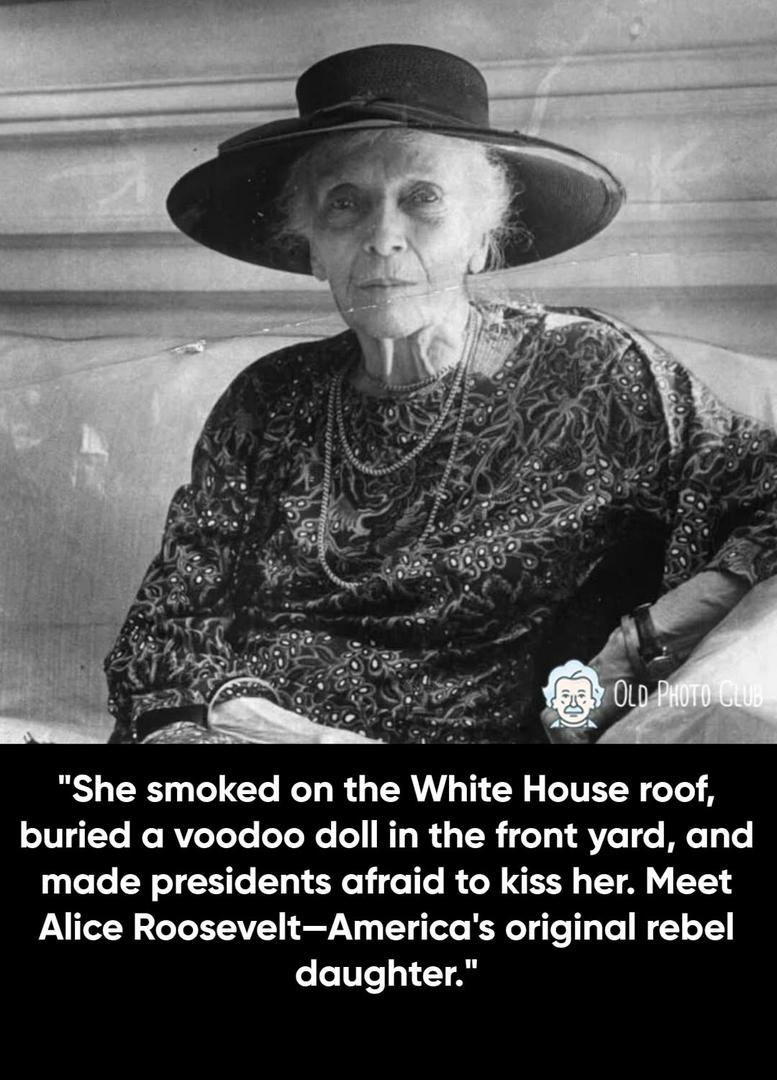

Alice Roosevelt didn't enter history politely. She burst into it—laughing, smoking, and shattering every rule Washington thought it had. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, his seventeen-year-old daughter became the most famous young woman in America. The press crowned her "Princess Alice." Newspapers chronicled her every outfit, every joke, every scandal. And when she wore a particular shade of blue-gray so often that manufacturers started producing it, America named the color after her. They called it "Alice blue." But Alice had no interest in playing the demure First Daughter. She smoked cigarettes in public—shocking for any woman, unthinkable for a president's child. When her father forbade her from smoking under his roof, Alice simply climbed onto the White House roof and lit up there. "If he said I couldn't smoke under his roof," she shrugged, "I decided to smoke above it." She raced cars through Washington streets. She stayed out past dawn. She gambled. She rode in automobiles with men—without a chaperone. She carried a pet snake named Emily Spinach in her purse and would release it at boring dinner parties to liven things up. The French press tracked her social calendar like a sport: 407 dinners, 350 balls, 300 parties—in just fifteen months. Exasperated beyond diplomacy, President Roosevelt once confessed to a friend: "I can either run the country or attend to Alice, but I cannot possibly do both." And that was the magic of her. She never asked permission. She simply lived—vivid, unscripted, unstoppable. When the Roosevelts left the White House in 1909, Alice buried a voodoo doll of the incoming First Lady, Nellie Taft, in the front yard. The Taft administration promptly banned her from the premises. President Woodrow Wilson banned her too, years later, after she told a joke about him so wicked that no newspaper dared print it. Washington couldn't stay angry at her. It needed her. For six decades, Alice's drawing room on Massachusetts Avenue b

2025-12-18

Just my Opinion

Really? Who gives a shit?

12-20

San Andreas, CA

Reply

2

More comments ...

write a comment...